What on Earth are Rare Earth Elements REE’s – Part Two

Rare Earth Elements – Part Two

As mentioned in Part One, rare earth elements (REE) are all the rage at the moment. Explorers are looking for new projects with rare earth element potential and reassessing existing projects in their portfolios for possible unrealised rare earth element potential.

Exploration teams are using their knowledge of rare earth element mineralisation and information gleamed from known rare earth element deposits to advance their efforts.

In this article, I’ll summarise the main types of rare earth element deposits so that you might understand the strategy of exploration (where, how, why) and the subsequent results.

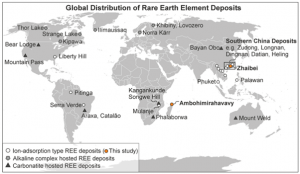

At a very high level of classification, there are three types of earth element deposit that are divided on the basis of host-rock.

Alkaline granite hosted deposits

Carbonatite hosted deposits

Clay-hosted, or Ion-absorption type deposits

Map from A.M. Borst, et al 2020 Adsorption of rare earth elements in regolith-hosted clay deposits.

Alkaline granites are igneous rock that have relatively high levels of potassium feldspar. These types of feldspars are typically pink/red and so alkaline granites are recognised by being pink or red. Pegmatites, which are more familiar in lithium exploration, are a coarse-grained alkaline granite.

A typical red alkaline granite.

A typical red alkaline granite.

Syenites and nepheline-syenite granites are also considered alkaline granites.

Carbonatites are also igneous rocks but are quite rare because they have a relatively very high proportion of carbonate minerals. Due to their low degree of partial melting, they have an odd-ball geochemistry, including rare earth elements.

Carbonatites typically occur as intrusions, forming ringed structures that not unusually form isolated hills, even mountains.

The clay-hosted or Ion-absorption type deposits are essentially formed through the weathering of rare earth element-bearing alkaline granites and/or carbonatites and the reconcentration of the rare earth elements in adjacent clays.

So…. in very simple terms, there are three main host rocks that are prospective for rare earth elements: i) certain red alkaline granites, including pegmatites, ii) “odd-ball” hill-forming intrusive carbonatites and iii) clays that come from the weathering of i) and ii).

The rare earth elements are elements that do not occur in native (pure) forms like gold, and sometimes silver and copper can for example. Rare earth elements occur in minerals within the host rock.

What are the common rare earth element bearing minerals and how do these minerals occur in the important rare earth element deposits and prospects of Australia?

In the Australian rare earth element exploration sector, two of the frequently mentioned rare earth element minerals are as xenotime and monazite.

Xenotime (chemical formula: YPO4) is an Yttrium (Y) Phosphate (PO4) mineral that is found in pegmatites. It forms a solid-solution series with chernovite. This simply means that under certain conditions Xenotime can turn into chernovite with the addition of arsenic – YAsPO4.

Secondary changes of Xenotime can see Yttrium (Y) being exchanged with the rare earth elements Dysprosium (Dy), Erbium (Er), Terbium (Tb) and Ytterbium (Tb).

Monazite is also a rare earth element phosphate mineral, with unimaginative names like: Monazite-(Cerium) = Ce(PO4); Monazite-(Lanthanum) = La(PO4); Monazite-(Neodymium) = Nd(PO4); and Monazite-(Samarium) = Sm(PO4).

This is where is gets interesting. Monazite is part of group of minerals called the anhydrous phosphates which includes xenotime, monazite (both described above), and also lithiophyllite (a lithium manganese phosphate – Li MnPO4), and purpurite (a manganese phosphate – MnPO4). Phosphate gets quite a mention!

In certain pegmatites we are seeing xenotime/monazite with rare earth elements, phosphates and lithium.

It is not surprising to know that many of the locations prospective for rare earth elements are also prospective for phosphate. This is born out in the largest and most prospective rare earth element deposits in Australia, Lynas’s Mount Weld Mine in Western Australia, and Arafura’s Nolans Bore Deposit in the Northern Territory.

FYI: Uranium mineralisation is also very commonly linked to rare earth element and phosphate mineralisation.

In Part Three I’ll talk about Mount Weld and Nolan’s Bore. The geology, mineralisation and reserves.